The Law is the subject of this final instalment because of its status as a key institution responsible for much of what is universally regarded as unique and desirable about western civilization.

It is an historical anomaly to be able to walk into a court and expect that the judge will base their decision not on the intellectual fad or personal preference of the day, but on an independent body of doctrine and principles that guard against the use of narrow prejudice; that a defendant would be innocent until proven guilty; that everyone has a right to a fair trial – all of these things mark out the law as it has developed over the course of millennia from Greece to Rome, Britain and beyond.

Overview

In this piece, I’ll contrast the common law and its grounding in natural law, with contemporary movements and their intellectual underpinnings. The forces that have constituted a countervailing trend in the intellectual domain are best thought of as constructivist, and rationalist in nature. That is to say, principles and values are ultimately constructed by human communities, and therefore somewhat arbitrary and contingent. Rather than precedent evolving and emerging in specific and local contexts, laws and regulations are to be designed and imposed rationally from the top down, and cover more jurisdictional space without regard for the particularities of the place onto which they are imposed. Immanuel Kant, and his contemporary influences John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas best exemplify the philosophy motivating this view.

Kant and followers, who built upon his relatively slim political writings, which were never the focal point of his philosophy.

Lastly, (in the next instalment) I’ll look at how these different historical trends are embodied in contemporary legal philosophy. Legal positivism is the idea that law does not contain any necessary connection to natural law and justice, but is simply a fact that demands coercion and obedience. The most common way to understand and apply the law is through the ‘interpretivist’ framework, in which interpretation of the law in many cases goes beyond ordinary meaning, existing precedent and foundational documents to include the ‘intention’ of authors, the contemporary culture, and more. The approach to understanding the constitution that follows is to see it as a ‘living’ document, that must constantly be reinterpreted in light of changing values.

Today, the courts are increasingly seen as a battle ground in the culture war. Naturally so, for progressives came to recognize that the law is inherently conservative, as it is a body of doctrine, with rules and principles grounded in precedent and practical reason. It is thus a barrier to their hoped-for otherworldly reforms that know no bounds.

The United States Supreme Court has seen some of the most dramatic culturally and politically sensitive cases. This politicization of the court is something that other countries like Canada have avoided, but I will argue that it is only because the progressive principles of vagueness and relatively are already heavily embedded therein.

Finally, I will point to the principles that must be recovered if the law is to endure and adapt to changing circumstances – metaphysical realism, natural law and natural rights.

The Common Law and its Foundation in the Natural Law

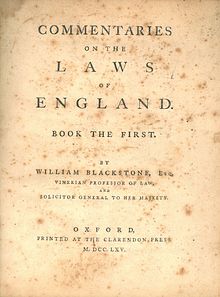

Commentaries on the Common Law, by William Blackstone in 1765.

The Common Law began in England. It is ‘judge-made law’, rather than law by statute or regulation. It is built upon and subservient to existing precedent, and develops on a case by case basis. When the specifics of a particular case that a judge is presiding over confound the existing body of doctrine that constitutes precedent, the judge may synthesize and remake the body of law so as to resolve the tension and set a new precedent to incorporate the circumstances in the case at hand. So on and so forth.

The Common Law is supposed to be especially attuned to the real circumstances that people find themselves in at any given time. Thus, it holds an advantage over laws that are made at a distance by legislation in government, or regulation by the executive or administrative branches. These decision-makers are necessarily too removed to be aware of the myriad facts and circumstances on the ground in a given locality, region, province, or state to properly comprehend the issue at hand.

Secondly, it is supposed to guard against human failings because the judge must subordinate their opinion to the body of doctrine. Only in cases of incongruousness with the existing body of law can the judge set new precedent.

Now, precedent must have its beginning somewhere, as does any body of law – Roman, Civil, Babylonian, or what have you. In the West, this has been Natural Law, something articulated in the Old and New Testaments, Plato, Aristotle, and Roman intellectuals such as Cicero. It was thoroughly developed and popularized by figures in the Scholastic movement in the Middle Ages – Albert the Great and St. Thomas Aquinas.

Though it has been the subject of much intellectual effort to flush out and justify the tenets of such an approach, its roots are grounded in that which is universal, down to earth, and practical. The natural law is made up of those precepts that are accessible to humans at all times and all places through both an informed conscience and reflective reasoning about what activities are good and bad for humans to engage in.

It necessarily depends upon normative conceptions of individual and collective human purpose. For Aristotle, human goodness is flourishing. It is a functional concept that involves the use of reason to act in such a way so as to acquire virtues, and embody them in stable character traits. The cultivation of good habits – intellectual, social, and so on – enables one to pursue the good.

Aristotelian virtues are stable character traits developed by cultivating habits through the use of reason in accordance with one’s nature. The virtues represent the ‘mean’ between excessive and deficient behaviour. They are dependent upon context, but are universal in their applicability. The person that develops stable character traits, and practices the virtues leads a ‘flourishing’ life. It is sometimes translated as ‘happiness’, but since that word is relative and refers only to ‘pleasure’ in contemporary culture, it is better to think of it as deep fulfilment, and lasting contentment.

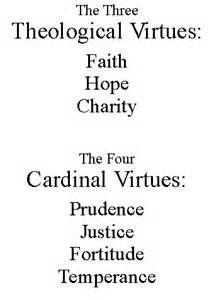

For St. Thomas Aquinas, humans are made in God’s image. To the classical virtues, he adds the theological virtues exemplified in the New Testament, and articulated by the church in its infancy – faith, hope, and charity (love).

To the four cardinal virtues were added the three theological virtues by the early Church fathers.

The natural law is not to be explicitly laid out in the form of strict rules, but is to inform the practice of lawmaking. Laws must be made in such a way so as to enable the human person and community to live up to their purpose, by living in accordance with objective values in the pursuit of flourishing.

Though it has taken many centuries to develop this enabling character of the law, its seed is fully contained in the Christian heritage, which sees God as loving – and by extension humans, made in God’s image – at the heart of the meaning and purpose of life.

The term ‘love’ does not refer to a simple, or discrete and short-term psychological state of affection, desire or attachment, but is an enduring disposition of other-regard. To love another is not to be ‘nice’, or to always accept whatever it is that they do. It is to wish for their good, and to help them achieve it. Here, ‘good’ is not simple and subjective, but that which is conducive to human flourishing.

Everyone knows that love cannot be coerced, and must be freely chosen and entered into. That is why law has, in the West, slowly developed and centred around the protection of the divine individual, whose dignity and integrity is the necessary source of all that is good.

Kant and his Descendants

Constructive Rationalism supplants Realism

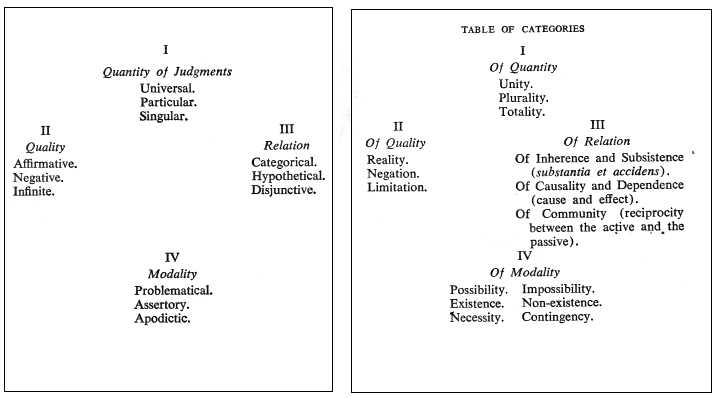

Immanuel Kant gave the fullest expression to the more Rationalist side of the Enlightenment. He sought to salvage the Aristotelian Metaphysical categories by assigning them a new home – the transcendental subject (or, the forms of our experience). He argued that it could not be demonstrated that the content of a concept is something that can be extricated from the contributions of our faculties of sense and intellect. It thus could not be shown that there are concepts ‘out there’ independent of the way in which it is experienced. The categories through which we understand all phenomena – the senses, the intellect, and the imagination – do not correspond to objective features of a mind-independent reality but are the necessary forms of our experience itself.

Aristotle’s categories describe all of the ways in which a thing can be, or exist. He organizes it as a list of what sorts of things can be said about subjects (the properties or predicates that a subject can have). For him, these ‘subjects’ are ‘real’, hence Realism about metaphysical concepts.

Kant’s categories take what Aristotle laid out and conceives of them in relation to the mental operation through which we come to sense, or cognize the objects of our experience. The categories are therefore not ‘real’, but functions of the relationship between the way in which we experience things, and the content of that experience.

Since we cannot demonstrate – according to Kant’s standards – a neat contrast between the things that we bring to bear in shaping and understanding our experience, and that which is independent from it, we cannot have certain metaphysical knowledge.

Metaphysics – what seems like an abstract and distant domain with no real world application is in fact the most practical one. This is because all of the concepts we deploy in our systems of language, theories, and ideas have core elements which may be most accurately described as metaphysical.

There is no empirical sense datum that leads us to the conclusion that the law of non-contradiction is true. We cannot see, or empirically demonstrate that every thing is itself and not something else (the law of identity), or that time moves from past to present and future. All of our language is shot through with concepts the likes of which are not what so many contemporary people think they are – ‘scientific’ in some way or another. They are inherently ‘meta’ (beyond or above) the physical. They are ways in which we understand and classify our experience, but are not necessarily ‘out there’ or perfectly derived from it.

To a psychologist who says that there is a neatly definable entity referred to as a psychological ‘disorder’, or an environmental scientist who uses the term ‘biodiversity’, insisting that it is a thoroughly quantifiable, ‘scientific’ term – it must be pointed out that they rely upon inherently normative distinctions through and through.

The ‘order’ that is required for the term ‘disorder’ is rooted in an idea that there is good and bad human functioning. The idea that biodiversity is good or bad for the environment or an ecosystem presupposes the idea that there is a good, or desirable one to begin with. The fact that these terms are founded upon beliefs about ‘value’ go to show how blatantly false the popular understanding of value-free science, reason, and rationality truly are.

The Constructivist-rationalist understanding of knowledge, inference and evidence has led to the bracketing of questions about the evaluation of the normative principles upon which systems of thought, action, and worldviews depend because of a deep scepticism about the reality of the ‘value’ concepts that we employ.

This view – which predominates among many in the West today – has distinctly Kantian dimensions. For Kant, the reason why we should believe in all of the metaphysical concepts that shape our thinking is because they make thought and action possible – they are pragmatically useful.

Today, most are not even this strongly committed to the existence of values, regarding them and particular ways of thinking as purely contingent, and wholly determined by social and natural causes. The argument in support of this belief is essentially that our own ways of thinking and knowing are caused by solely external factors (neurons, physical processes, social factors, our evolutionary heritage, etc.), denying the belief in ‘mind’, or anything first-person as a cause. This renders all values unnecessary and arbitrary because they are the result of ‘forces’.

There could certainly be no better or worse ways of thinking or acting on this view, because value terms are all determined and emerge differently in every person, culture, time and place.

All that said, the Kantian strain of modernity – though not the postmodern – clings to rationality and objectivity by arguing that these values and concepts we’ve come up with are the inevitable ways of thinking and acting (forms of cognition, understanding, and sensation) that we cannot deny on pain of contradiction. We must therefore continue to believe in the objectivity of morality, purpose, reason, and empirical science, though we are sceptical about their ability to answer deeper questions. It is this scepticism about values, but willingness to retain many of them, that the majority of the more moderate progressives and liberals practice today.

Contemporary Kantians – Rawls and Habermas

Two social and political philosophers who have done the most to extend this Kantian spirit into the 20th and now 21st century are John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas.

John Rawls sought to update the social contract, taking it from its context in a philosophical era that framed the search for knowledge around the isolated consciousness – Descartes’ cogito – to one that attempts to consider the larger community as the standard of justification.

He sought to elucidate the most coherent foundational political principles, by envisioning what people would agree to if they were placed in an unbiased situation.

In an Original Position, behind a Veil of Ignorance, the rational social contractarian would consider how they would want the social and political principles of the polity to be laid out. The nature of the position, and the constraints facing the deliberators are supposed to be such that the principles decided upon would be just and fair.

The two principles that he thinks would result from such a process are:

“First Principle: Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all;

Second Principle: Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions:

- They are to be attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity;

- They are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle).” (Justice as Fairness, John Rawls; pgs. 42–43)

Rawls thought that it is rational for people in the original position to order the political system according to these two principles because of their ignorance about their own starting position and natural talents and abilities.

The first principle is easy enough to understand – you would want as many freedoms as possible, so long as they do not contradict those of others. The second principle is based on a kind of prudential calculus – since you don’t know anything about yourself or others, it would make sense to arrange things such that differences are ordered and compensated for in such a way that it is in the best interest of the least well off.

Of course, this looks ok on the face of it, but in reality none of the terms used in the theory are easy to operationalize. What does a ‘fair equal opportunity’ mean, and is it even possible to arrange that, especially without sacrificing the most basic freedoms? Many have argued that the answer is a clear no. What does ‘to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members‘ mean? That they have more opportunity, respect, wealth? Who knows. Can you socially engineer more ‘respect‘ for people? Who would really think so? Unfortunately, it is a default position for many today.

Furthermore, Rawls seems to assume a strong correlation between what he considers the unearned – and therefore unjust – ‘natural talents and abilities’, and success in all domains. It is clear that there are many people who are very smart and talented, but very depressed, unhappy, do not hold high office, power, or make a lot of money; and then many who are vicious, and narrowly talented, but massively wealthy, hold high status, and so on. In short, the categories he considers desirable are not correlated with the things he considers ‘unjust’, and that should therefore be the subject of ‘redistribution’.

The premise upon which this social contractarian thought experiment is based is that there can be no agreement about fundamental moral and social goods, so we must settle for an overlapping consensus on those values. Our beliefs must settle into a reflective equilibrium with those of others after the process of democratic deliberation, which, naturally, could never generate consensus because of its place in a society hollowed out of its common core. Claims made in the ‘public sphere’ would have to be articulated in terms that are publicly understandable, and thus religious or particularized claims would have to be secularized and generalized so that they could be expressed ‘publicly’.

Habermas – Unofficial Philosopher of the European Union

Habermas is the European counterpart to Rawls. He comes from the German Marxist tradition that, after it became clear that Classical Marxism was false on many levels, recreated itself as Critical Theory.

Habermas’ teachers, Adorno and Horkheimer thought that Enlightenment Rationality was fundamentally ‘instrumental reason’ – something that tried to fit everything into the mold of efficiency for the sake of utility maximization. They were not wrong in the sense that so many people today do engage in this type of thinking about things as diverse as their careers, to their relationships.

Habermas rejected the path they were going down because it was a kind of complete scepticism about reason, philosophy, and much of the Western heritage. Adorno in particular sought to replace the lost sense of purpose and values with the subjective experience of aesthetics – music, art, and literature in the modern and postmodern fashion.

Like many philosophers in the 20th century, Habermas shifted after the decline of the philosophical paradigm of consciousness to the paradigm of language. Unlike the Anglo-American Analytic Philosophers focused on language as a syntactic or semantic system, Habermas turned to the analysis of language in use in speech and action.

As Kant viewed the assumptions we make about the forms of our experience to be pragmatically useful, but fundamentally untrue, Habermas does the same with the forms of our speech and action, and the assumptions we make implicitly by engaging in them.

The person engaged in practical action and communication with others makes different types of claims depending on their goals:

- a claim to truth raised in constative speech acts;

- a claim to normative rightness raised in regulative speech acts;

- a claim to authenticity or truthfulness raised in expressive speech acts

These claims can only be made intelligible on the basis of implicit assumptions. When you state a fact, or make an assertion, you implicitly assume that what you say is true. When you say that someone should or shouldn’t do something, or that something is good/bad, tasty, ugly, beautiful (all ‘normative’ claims), then you assume that there are reasons that could be given to defend what you say. When you express your preference or opinion about something, you implicitly assume that your statement corresponds to an inner state of mind that you have. Therefore, your assertion could be sincere or insincere, and there are ways to discern whether or not this is the case. Otherwise, communication would be impossible, or not really what we think it is, or act like it is, so Habermas argues.

Just as Kant called the categories of experience and of understanding ‘transcendental’, Habermas calls these ways of speaking and acting ‘transcendental’ in the sense that they are necessary features of all speech and action of the particular type that they correspond to. He proceeds to build a social and political philosophy from this framework that recognizes the importance of communication done in accordance with these ‘necessary assumptions’.

Having moved beyond Kant to recognize truth as something that must emerge from the process of deliberation and the exchange of ideas, constrained by the forms of reasoning appropriate to them, Habermas thinks that many of our forms of social organization, economic, legal, and political institutions must become more deliberative.

There are norms of rationality and argumentation implicit in the types of claims we make and actions we undertake in concert with one another. When we do not reproduce our common life through these modes of interaction, the social fabric disintegrates:

“Social pathologies are not the inevitable consequence of rationalization per se but result rather from a lopsided process in which the market and administrative state invade the lifeworld. Displacing modes of integration based on communicative reason with their own form of functional rationality.” (53)

The Theory of Communicative Action, Vol. 1 : Reason and the Rationalization of Society (1984); Jürgen Habermas, Polity Press, pg. 53

He applied this linguistic social theory to the political realm in more recent years. In Between Facts and Norms, he searches for the ‘translation mechanism’ that is required to change the public opinion formed in workplaces, social, civic, associational and family life into the organizations, and institutions of society. He finds it in the rule of law.

In a society that is both modern and pluralistic, like Western ones, people do not agree about most things, believe in fewer common values, and do not engage in social life as they once did, so something must stand in as the socializing force. It must also recognize the equal personal freedom, and democratic participatory rights that freedom entails, so it must be legitimate and connected to popular sovereignty. Habermas thinks therefore that the law-making process must become more democratic, while remaining grounded in reason and rationality of a kind that would not be found at the coffee shop, or around the dinner table. It may then serve as the legitimate translation mechanism of the freely formed public opinion in civil society, while guarding against the fundamentally populist nature of such a discourse in an increasingly ideologically diverse, and even valueless society.

Habermas (on the left) was and still is a public intellectual of the highest standing. He left no stone unturned and engaged all of the intellectual currents in society – a true philosopher. Here he is with then-Cardinal Ratzinger discussing the nature of the justification of religious claims.

For our purposes, Habermas’ view of the law stands directly in contrast to the realist understanding of truth and its manifestation in natural law and natural rights. He sees truth as fundamentally the product of different types of discourse, where the truth, rightness, or authenticity of a claim is contingent upon a hypothetical consensus. Claims about what is fundamentally good, right and just must always be remade, and are grounded only in the shifting forms of agreement that we only ever notionally ascribe to.

His view of the law as translation mechanism is supposed to avoid technocracy and the hollowing out of democratic and personal freedom by an ever-greater expansion of the administrative state, but it is more of the same.

First, it is not even remotely possible to legitimately translate a vague and incoherent ‘public opinion’ into law in a top-down fashion through the courts and legislatures. For, this kind of law is fundamentally abstract and removed from both the territory that it must cover, and the genuine wishes of the people that supposedly motivate and guide the changes with their loosely expressed opinion.

Furthermore, it is idealistic in the extreme to suppose that both a) there can be such a thing approximating informed consensus in a society based on value pluralism, and b) that its imposition through the courts and legislatures would be legitimate, and not another form of more egregious state coercion.

Here, Habermas asks German Minister of Foreign Affairs Sigmar Gabriel and then French Presidential Candidate about Europe’s future, suggesting that they must become even more politically intertwined.

Today, he is in many ways the unofficial philosopher of Cosmopolitanism, Political Globalism, and the European Union. He argues that due to increasing connectedness, and the transnational problems that result, there must be newer, thicker forms of political organization to deal with them.

He is no doubt correct in the analysis that with more interconnectedness, comes new problems that are outside of the scope of single countries. However, his institutional prescriptions are overreaching, and would be destructive of all forms of autonomy – personal, local, and regional. A further politically integrated EU, or United Nations, would look more like the USSR than the classical liberal nation-states of Great Britain, France, or the United States that have begun to sink under the weight of their bureaucracies, and deformed institutions.

The Legislative vs. the Organic

In his work, Law, Legislation and Liberty, Friedrich Hayek gave the clearest articulation of what is wrong with top-down, technocratic and legislative approaches to law-making. He contrasts judge-made law with law by statute and regulation, showing that the former is attuned to context, and prescribes appropriately as it is confined to a region in which it understands. Legislative or statutory lawmaking is necessarily biting off more than it can chew, unless it is simple, as well as general and abstract enough so that the principles it establishes are clear, but the specifics can be appropriately fitted to the context in question.

Habermas, and other left-wing thinkers want to expand the role of the government in creating more laws and regulations that are prescriptive and coercive, rather than negatively expressed. Laws that only describe what cannot be done create a simpler system, and leave room for a larger space to open between the law and morality. This space is essential for human character to develop and flourish, for the surest way to deprive action of its merit is to make it mandatory.

They do not seem to recognize that prescriptive legislation and regulation in overreaching fashion has already been working against the goals that they seek to achieve – an improvement in the material, and social conditions of the worse-off, the marginalized, the oppressed and the victimized.

A central plan is designed to yield an end-state. The plan aims to bring about particular outcomes—what roles people will play, what they will achieve in those roles, and what they will win by so achieving. By contrast, in what we should call spontaneous order, government provides a stable and known framework of rules.

Friedrich Hayek; the Road to Serfdom; 1944, pg. 113.

This is THE central difference between conservative and liberal and further left-wing politics in terms of approach to government. Conservatives want to set up a framework of guiding principles that do not prescribe behaviour, so that people may pursue their own path, and freely choose to live the good life in whatever particular manifestation is suited to them. Leftists and increasingly liberals want to prescribe an end goal, as well as all the steps in between. They want to tell you exactly where you’re going and how you should get there.

This is why it is a plain contradiction to join the words ‘democratic’ and ‘socialism’ together, as do so many young people and liberal and left-wing candidates today. There is nothing democratic about the thoroughgoing imposition of coercive laws, and ‘positive’ rights.

Impact on the Law

In law, the Rationalist thinking of the kind that Rawls and Habermas exemplify has shown up in a few ways.

First, there is a constant attempt to revise the principles upon which a body of law stands, as well as the practices of interpretation that make them up. This follows naturally from the idea that there are no foundational principles, and interpretation is ‘merely’ an art, and therefore something to be remade and repurposed.

Second, the idea that one cannot reason coherently about values themselves has led to the adoption of the two twin reductionist forms of reasoning in law – consequentialism and deontology, both increasingly unmoored from their embedding in natural law principles. The former shows up as the attempt to base legal rulings on some apparently definable and measurable consequences, and the latter as a strong, unwavering appeal to whatever the most important principles in the culture at any given time, even though these principles are arbitrary, and always changing.

Third, and somewhat confusingly, since there are no ‘real’ values, we can and should remake and refashion them so as to constantly ‘progress’. This follows from the assumption that reason is always discovering and progressing, not new ways of embodying timeless values and principles, but of inventing new ones. I say confusingly, because this clearly makes no sense in light of the point from which such a view begins – a repudiation of the idea that there are such things as better or worse foundational values that can be known, and followed.

Since the human heart naturally longs for the good, the true, and the beautiful, this modern scepticism and ‘rationalism’ has left us anxious, and searching. We therefore turn to wonky new ideologies and pursue them with tremendous zeal, in an attempt to overcompensate for the gaping whole that is left in our meaningless lives.

The Climate ‘Emergency’ movement – mass hysteria. When things have never been better materially, but there’s nothing to work towards because you don’t believe in anything, people need an outlet and a cause to believe in. Outrage fills the hole.

Many people are engaged in a frenzied, and zealous pursuit of change for the sake of change, often under the banner of a new ’cause’ or ‘-ism’ – new age spirituality, healthy living, environmentalism, some form of collectivism, socialism, or the pursuit of ‘experiences’. The belief that motivates the modern person to put their faith in the fulfilling potential of any one of these practices is due to the intuitively plausible inference that conflates our ability to make technological and scientific advancements with the capacity to improve the fundamental character of human nature itself – the struggle to attain happiness, the good and fulfilment while warding off pain and evil. To pursue goods in light of finitude and many failings and shortcomings is the very form of human existence itself, not something that can be altered.

The worldview that seeks change and thinks highly of its own philosophy is the most dangerous of all, for it promises so much that is logically impossible and antithetical to our deepest longings. Because it is also accompanied by great hubris and hope, it therefore frustrates the most. Witness the progressive uproar and extreme intolerance of ‘reactionary’ conservative ideas that are enjoying their 15 seconds in the sun at present.

In the next section, I will explore how the forces that fly together under the banner of emotion and reason – progressivism and constructive rationalism affect the approach to legal interpretation, and lawmaking itself.

I will end by pointing to principles and practices that are more conducive to the preservation of freedom, and the enabling of human flourishing in line with universal values and classical virtues.

Suffice it to say, that view is rooted in natural law, practical reasoning that is informed by the values that are embodied therein, and respectful of the division of powers in republican and democratic regimes in which the government serves the citizens, not the other way around.

[…] Finally, I will point to the principles that must be recovered if the law is to endure and adapt to changing circumstances – these being realism, natural law and natural rights, concepts that I described in parts 2 and 3. […]

LikeLike

[…] – how negative rights have devolved into positive ones and how they are used in politics. In the third and fourth, I examined the philosophy of law, the common law tradition as it is grounded in natural […]

LikeLike